Historical Sociolinguistics and Sociohistorical Linguistics

Up |

Henry Fowler and his eighteenth-century predecessors

Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade (contact) (University of Leiden) Received October 2009, published December 2009

1. Introduction1 Henry Fowler (1858-1933), whose date of birth 150 years ago was commemorated at this year’s annual colloquium of the Henry Sweet Society at the University of Nottingham, is not listed in the Lexicon Grammaticorum (Stammerjohann 1996). He does have an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), where he is described as a “lexicographer and grammarian”. The picture accompanying the entry shows him as an elderly man kneeling beside his dog. The contrast with the picture of Fowler in Crystal’s Encyclopedia of the English Language (1995:196) is striking: there, he is portrayed in his swimming gear. On the face of it nothing seems wrong with this, for Fowler was an active swimmer all his life (McMorris 2001:9). But it is not his ability to swim that earned him a section in the encyclopedia or indeed in the ODNB but the fact that he was the author, together with his brother Francis, of The King’s English (1906), the Concise Dictionary of the English Language (COD) (1911), and, after Francis’ death in 1918, of Modern English Usage (1926). With The King’s English appearing in a third edition in 1931 and being reprinted down to 2002, the COD being published in its ninth edition in 1995 and Modern English Usage in a third editon in 1996, these popular books are a considerable achievement by any standard. To depict their author in his swimming gear - no other writer on English grammar is shown similarly in the encyclopedia - doesn’t, in my opinion, do him justice. It is emblematic of the kind of treatment Fowler is often subjected to. Despite the disparaging picture, Crystal writes that Fowler’s Modern English Usage is “often referred to in the revered tones which one associates with bibles” and that it is “the apotheosis of the prescriptive approach” to language (Crystal 1995:196). The same kind of mixed attitude to Fowler and his work can be found in Burchfield’s preface to the third edition of Modern English Usage which was published in 1996, where he describes Fowler as “a legendary figure”, stressing at the same time “the isolation of Fowler from the mainstream of linguistic scholarship of his day” (1996:vii). Burchfield calls the work a “fossil” (1996:xi). As for Fowler’s own view of himself, Jenny McMorris, in her excellent biography called The Warden of English. The Life of H.W. Fowler (2001), quotes him saying: “I am no true lexicographer; the only parts of the science I care about ... are grammar & idiom” (2001:195). And that is indeed what Modern English Usage is: an alphabetically arranged collection of usage problems relating to grammar and idiom. A small survey I carried out this Spring among the members of the Henry Sweet Society showed that Fowler’s Modern English Usage isn’t used much, by the participants in the survey at least, and that if it is, it is not in its function as a usage guide but as an object of linguistic analysis. What is more, the book produced particularly negative reactions among the informants. All this suggests that historical linguists do not make up the book’s readership. And yet Fowler’s Modern English Usage has been popular ever since its appearance: according to McMorris (2001:178), when the book came out in 1926 as many as “10,000 copies were sold in the first three months and 60,000 in its first year”. This is astounding, especially considering the fact that its reception had been rather mixed. Evidently, its publication answered a real need. In 1965 a second edition was published, revised by Sir Ernest Gowers, and there was a third edition in 1996 by R.W. Burchfield. This year, a reprint of the book came out as part of the Oxford World’s Classics series with an introduction by David Crystal. Who, then, reads Fowler’s Modern English Usage? What is the audience for whom this usage guide was written to begin with and who has been buying the book in such numbers since its first appearance? Burchfield, in his introduction to the third edition, asks the same question: “why has this schoolmasterly, quixotic, idiosyncratic, and somewhat vulnerable book ... retained its hold on the imagination of all but professional linguistic scholars for just on seventy years” (1996:ix)? If linguists are, indeed, not part of the book’s audience, who are? In the course of his preface, Burchfield refers to three typical users of the book: “a judge, a colonel, and a retired curator of Greek and Roman antiquities at the British Museum”, all of them, I would say, elderly, middle-class fairly educated (male?) professionals, and all of them the kind of people who evidently feel the need for linguistic guidance, who seek reassurance as to what is correct usage by resorting to their Fowlers to have access to a norm of linguistic correctness. None of Burchfield’s labels are, I think, positive qualifications of Fowler’s Modern English Usage. What makes the book vulnerable in Burchfield’s eyes seems to be the fact that usage guides like Fowler’s are generally disparaged by modern linguists as unscientific. They are blamed for dealing with language at the level of usage rather than as a system, and for the fact that in doing so they take a prescriptive rather than a descriptive approach (see Pullum 1974). A good if somewhat shocking example of this can be found in the controversy between John Honey and Peter Trudgill upon the publication of Honey’s book Language is Power (1997).2 It is this attitude to writers like Fowler, I believe, that gave rise to his portrayal as a swimmer rather than as a writer on language, as someone to be taken less seriously than grammarians like Robert Lowth, Lindley Murray, Noah Webster and others. The label “schoolmasterly” seems to refer to Fowler’s attempt to correct the language of those for whom he wrote his book, and “quixotic” to the fact that, in striving after the ideal of linguistic correctness,3 he is fighting a losing battle. This is an interesting point, because the battle Fowler is fighting, if indeed that is how it can be seen, had been going on since the eighteenth century, when we can see the rise of a canon of prescriptivism, including many items which still occur in Burchfield’s revision of Modern English Usage produced some 250 years later. It is striking that Lowth, who is often seen as the one with whom prescriptivism first began, talked about his grammatical efforts in a letter to his friend and fellow scholar James Merrick in similar terms:

The argument was about whether a prescriptive or a descriptive perspective should be taken when dealing with matters of divided usage - an enlightened and enlightening discussion - and Lowth here defends the approach he had taken in his grammar (cf. Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2006). As for the final label used by Burchfield, “idiosyncratic”, it is the aim of this paper to show that this was far from the case, and that Fowler is part of a tradition that has its roots in the eighteenth century and that can be linked with Lowth’s Short Introduction to English Grammar of 1762, which is treated by modern linguists with as much disdain as Fowler’s Modern English Usage. 2. English Shibboleths A well-known user of Modern English Usage was Sir Winston Churchill. When “planning the invasion of Normandy,” as McMorris writes on the final page of her book (2001:217), he “snapped at an aide to check a word in ‘Fowler’.” According to the ODNB, Churchill is believed to have been “academically a bit of a dunce”; perhaps, too, he felt linguistically insecure enough to need his Fowler, even in times of crucial action. Churchill is often cited as producing the hypercorrect “This is the sort of thing up with which I will not put!” (Crystal 1995:194). What he was trying to avoid here is known as preposition stranding, the kind of sentence in which a preposition follows rather than precedes the nominal it belongs to. (The sentence Churchill was allegedly trying to avoid, “... the sort of thing I will not put up with”, is not of course an instance of preposition stranding but of a phrasal verb.) Burchfield describes the stricture against preposition stranding as “one of the most persistent myths about prepositions in English” (1996:617), noting that it originated with Dryden in 1672 and that it “became entrenched” in the language subsequently. He refers to Lowth’s grammar4 as an example of how “the grammarians” discussed the phenomenon as being typical of informal language “rather than of error”. Burchfield’s “final verdict” on preposition stranding is that “in formal writing, it is desirable to avoid placing a preposition at the end of a clause or sentence”, though he adds that “there are many circumstances in which a preposition may or even must be placed late” (1996:619). This is exactly as Lowth had phrased it 234 years before - but much had happened in the meantime (see Yañez-Bouza 2008). Another shibboleth in English, considered to be among the worst of its kind (see Beal 2004:111-112), is the split infinitive, as in to madly love, to really and truly love (Burchfield 1996:736). The rule against the split infinitive is popularly attributed to the influence of Latin on normative grammar, the reason given being that in Latin infinitives cannot be split and therefore should not be split in English either. The stricture is also popularly - but wrongly, as it happens - attributed to Lowth (see §6 below). In the first and second editions of Fowler (not in the third) the phenomenon is treated as follows. English speakers can be divided into the following five categories: “(1) those who neither know nor care what a split infinitive is; (2) those who do not know, but care very much; (3) those who know & condemn; (4) those who know & approve; & (5) those who know & distinguish” (1926:558; 1965:579). This suggests quite a humorous approach to the subject, which is not untypical of Fowler, whose attitude to grammar is characterised by occasional “elegant flippancy”, as he referred to it himself in relation to the tone of the earlier The King’s English (McMorris 2001:59). In his rigorous editing of Modern English Usage, Burchfield did little justice to Fowler in this respect. Strictures such as the one against preposition stranding and many more besides go back to the eighteenth-century normative grammarians, though not the one against the split infinitive, which is a nineteenth-century invention (Beal 2004:112; Tieken-Boon van Ostade forthc.). During the eighteenth century, the English language was first codified into grammars and dictionaries, not at the instigation of an Academy as in France, Italy or Spain (and later, Sweden), but as a result of the efforts of individuals such as Robert Lowth, a clergyman who became bishop of London after he had written his famous grammar - not before, as is commonly believed - and Samuel Johnson, whose Dictionary of the English Language came out in 1755 (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2000). Including John Walker, author of the Critical Pronouncing Dictionary (1791), Joan Beal refers to these men as “the great triumvirate of eighteenth-century guides to usage” (Beal 2003:84). Though the original aim, as expressed for instance by Swift in 1712 in his well-known “Proposal”, had been to “correct, improve and ascertain [or fix] the English tongue”, the codifiers gradually learnt that no living language can be fixed. For all that, according to Beal (2004:123), “they have left us with a legacy of ‘linguistic insecurity’”, and it is this, she argues, that explains the popularity of usage guides like Fowler’s Modern English Usage, as well as many other “semi-humorous, but seriously prescriptive” books, of which Eats Shoots and Leaves, A Zero-Tolerance Guide to Punctuation (Truss 2003) is a recent example. 3. The standardisation process We can explain the phenomenon discussed by Beal by looking briefly at the history of the English standardisation process. Perhaps the best known model of the standardisation process of languages is that presented by Haugen (1966). The model comprises the following four stages:

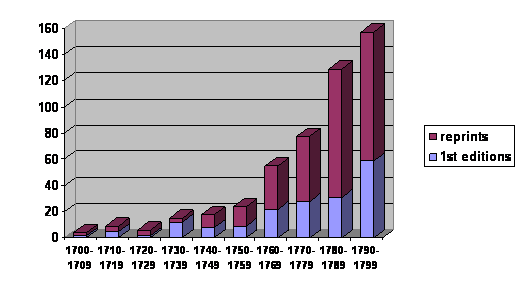

A more recent and at the same time more elaborate version of this model was put forward by Milroy & Milroy (1985), who use the notion of “standardisation” in a different sense than did Haugen. (Haugen deals with the development of dialects into languages, not with standardisation as such.) The model presented by the Milroys distinguishes seven stages in the standardisation process, i.e. selection, acceptance, diffusion, maintenance, elaboration of function, codification and prescription (1985:27), and in a different order from Haugen’s model. In the history of the standardisation process of the English language these seven stages closely reflect the linguistic developments from the beginning of the fifteenth century onwards, when a relatively unified formal written variety of English came into being, down to the eighteenth century, when the language was codified in grammars and dictionaries. Codification of the language in this account follows upon the elaboration of function stage, when the English language, during the Renaissance and the century afterwards, was adapted so that it could take over the functions of language that had formerly been the domain of Latin, particularly in the field of science and scholarship. (For a fuller discussion of this model in relation to the history of English, see Nevalainen & Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2006). The Milroy model has a further advantage over the Haugen one in that it includes an additional stage in the standardisation process, i.e. the prescription stage, which comes after the codification stage. This stage is of particular interest here, because it allows us to understand the popularity of Fowler’s Modern English Usage, both when it first came out and, still, today. The prescription stage started some time during the second half of the eighteenth century, and according to the Milroys is still going continuing, due to the fact that languages simply cannot be standardised (i.e. fixed) in the strict sense of the word (cf. the definition of “standard” in the Oxford English Dictionary). Once started, the prescription stage will never come to an end, and, today, we are therefore firmly entrenched in it. During the codification stage, which largely took place in the eighteenth century, English normative grammars were produced in increasing numbers, as is shown by Figure 1, the data for which derive from Alston’s bibliography of English grammars printed down to the year 1800 (Alston 1965). The figures also include the number of reprints of each grammar published during the period.

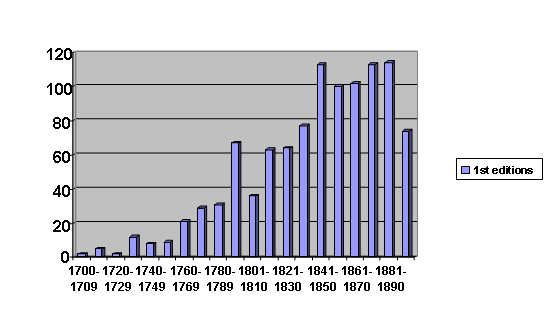

This growth in English grammar production continued into the nineteenth century, as is evident from the data presented in Figure 2, which combine the figures provided in Figure 1 for the eighteenth century (first editions only) with those presented by Michael (1991) for the nineteenth.5

So many grammars came out during the nineteenth century that Michael (1997) calls nineteenth-century grammar writing “hyperactive”: he argues that no new insights were gained during the period, that the grammars “were repetitive; many were merely commercial ventures, scholastically naive” (Michael 1991:11). The aim of the grammars, however, was not to develop linguistic theory, but to provide people with guidance on correct usage. In a society in which there was a lot of social mobility, this is what people needed. It is hard to say when exactly the prescription stage begins, and stages in a process like the standardisation process are rarely discrete anyway. But the figures provided above show that the phenomenal growth in grammar production of the nineteenth century started in the 1760s. Very soon after that, according to Leonard (1929), the first usage guide was published: Robert Baker’s Reflections on the English Language, in the Nature of Vaugelas’s Reflections on the French (1770). Usage guides are a typical product of the prescription stage, in that they offer specific guidance to anyone seeking access to the standard language, as previously codified in grammars and dictionaries. As the title indicates, Baker had based himself on the work by Vaugelas (1585-1650), one of the original members of the Académie Française for which he had written a book called Remarques sur la Langue Française (1647) (see Ayres-Bennett 2002). Baker evidently decided to write something similar for English. 4. Baker’s Reflections on the English Language Baker’s Reflections on the English Language (1770) is a curious and unique book which consists of 127 rules that deal with lexical and syntactic features (Vorlat 2001).6 The book is dedicated to the King, to whom Baker presents a plan for the improvement of the teaching of languages and also for the institution of an English Academy comparable to those in France and Italy. Such an academy, he believed, could cure the language of “Incorrectnesses and Barbarisms” in which “our Writers abound” (1770:i-ii),7 but a plea for an English Academy had not been heard since the first decades of the eighteenth century.8 Baker even had distinct ideas as to the kind of people that should make up this academy: eight “Gentlemen”, as he put it, from Oxford and six from Cambridge. But the academy never came about, not so much because Baker wasn’t heard, but because the idea of setting up an academy was already a thing of the past: many grammars had appeared since the days when people like Dryden, Swift and Addison had made a similar plea in the early years of the eighteenth century, but this was something of which Baker was unaware. He rightly, I think, claimed in his preface: “Such as my work is, it is entirely my own ... Not being acquainted with any Man of Letters, I have consulted Nobody” (Baker 1770:iv). He wrote, moreover, that he hadn’t even heard of a standard work like Dr Johnson’s Dictionary (1755) when he embarked on the Reflections:

Nor does Baker seem to have read any English grammars, which is peculiar, for by 1770 Lowth’s grammar had already proved to be extremely popular, and even Circulating Libraries possessed copies of it (Auer 2008). Like Fowler, therefore, Baker was evidently completely isolated from the “mainstream of linguistic scholarship of his day”, such as it then was. There is as far as I can tell no reason to doubt his claims in this respect.9 Baker is not listed in the ODNB, nor is there - as yet - an entry on him in Wikepedia. We know very little else about him apart from what he tells us in the preface, which is not much more than that he “quitted the School at fifteen”, and that he was consequently “entirely ignorant of the Greek, and but indifferently skilled in the Latin” (1770:ii). Though reminding us of Shakespeare’s “little Latin and less Greek”, this does not seem to be a humility topos: according to Vorlat (2001:394), Baker’s command of grammatical terminology, which he would have picked up as part of most boys’ formal schooling, is indeed very patchy. Normally, a skill in the classical languages would be the only capacity needed at the time for anyone who wished to produce a grammar of English (Chapman 2008), for English grammars in those days were largely based on the Latin tradition (Michael 1970). But undeterred by his lack of formal education, Baker continues on the same page, “Why should this incapacitate a Man for writing his Mother-tongue with Propriety?”. And this is what he proceeds to do. Reading his book in any case shows a more than impressive command of the subjunctive, as in “Though Every one be a Noun of Number, it has no Grace as a Plural” (1770:96). Baker’s Reflections are completely unordered, apart from the occasional associative link, as in the case of Rules xxvi and xxvii, the first of which concludes with a comment about the fact that “many People write I’le” instead of I’ll which leads him into the next item, starting with the words “The Mention of a double L puts me in Mind of a Mistake, that Writers often commit in speaking of a double Letter” (i.e. “a DD, or a double D ... a double DD”). One wonders how practical the book was to people seeking specific guidance in language matters. A typical example of Baker’s treatment of a particular feature is Rule xxii, Had retired for several Years past. His comment reads:

Baker’s approach is often quite humorous, as Fowler’s approach was, and perhaps for the same reason. In Rule xxx, for instance, in which he criticises the use of came as a past participle, he concludes: “If these Writers persist in this Use of the Word Came [as in He is Came], I would advise them, not to be inconsistent with themselves, to employ the Word Went likewise with the Auxiliaries, and to say He has went ...”, adding that “if we should bring them all to conform to it, we should have a new Language” (1770:30-31). On the forms our’n, your’n, his’n, of which he says that they are used by “infinite Numbers of the low People in the Country (and not a few in London)”, he similarly writes that he “would advise [his readers] likewise, in Imitation of many of those low People, to say Housen, instead of Houses” (1770:88).10 “Low people” are frequently criticised by Baker, in particular actors and servants (Vorlat 2001:396), but also newspaper language comes in for attack, as Rule xxii illustrates (see also xxxv, xliv, xlv, lxviii). This is interesting in the light of the “stylistic decay” of the medium which Görlach (1999:146) claims took place in the course of the nineteenth century. Görlach attributes this development to the time pressure inherent in newspaper production. Possibly, Baker’s criticism of newspaper language is an indication that this “stylistic decay” was also of a linguistic nature, and that it already occurred much earlier than Görlach suggests. Further research into this question, with the help of online historical newspaper databses would seem worthwhile.11 In being critical of newspaper language Baker agrees with Fowler, who according to Burchfield “[a]bove all ... turned to newspapers ... because they reflected and revealed the solecistic waywardness of ‘the half-educated’ general public in a much more dramatic fashion than did works of English literature” (1996:vii-viii).12 Baker wrote in his preface that in illustrating and discussing grammatical problems he “paid no Regard to Authority. I have censured even our best Penmen, where they have departed from what I conceive to be the Idiom of the Tongue, or where I have thought they violate Grammar without Necessity. To judge by the Rule of Ipse dixit is the Way to perpetuate Error” (1770:iv). Baker, in other words, was not a descriptivist. But he adds: “But don’t let the Reader imagine me vain enough to suppose my own Stile preferable upon the whole, or at all equal to that of some of the Writers, whom I have thus criticised”: he claims here that he did not adopt his own language as the norm of correctness which he presents in his book. Analysing Baker’s Reflections shows that, though poorly educated, he was an extremely well-read man. He refers to Shakespeare, Addison, Richardson, Swift, Lord Bolingbroke, Lord Shaftesbury, Congreve, Moliere, the correspondence between Locke and Molyneux, Pope, Harris, Shaftesbury, Fordyce and Warburton’s Preface to Shakespeare. These works he probably had access to through the Circulating Library to which he subscribed. According to Vorlat (2001:397) Baker classified authors into “bad writers, incorrect ones, tolerable ones, not so good writers ... good writers, and ‘our best authors’, ‘our most judicious writers’”. Samuel Richardson comes into his lowest category, for Baker considered his novel Pamela to be “emetic” (1770:10). Most of these writers, according to Vorlat (2001), were already dead, with one exception, William Melmoth (1710-1799). Baker presumably selected his examples carefully, to avoid offending living authors and thus create adverse publicity for his book. Baker may not be listed in the ODNB, but ECCO, or Eighteenth Century Collections Online, an electronic database containing more than 150,000 English books and their reprints published during the eighteenth century, contains two editions of the Reflections, both anonymous and each apparently representing a different print-run. ECCO also contains the second edition of the book which came out in 1779.13 According to Sundby et al. (1991:456), there are considerable differences between the two. All this shows that the book was moderately popular. Baker clearly wished to profit from this personally, as the second edition of the book is no longer published anonymously. But there are more books in ECCO by Baker, such as Observat. [sic] on the Pictures Now in Exhibition at the Royal Academy, Spring Gardens and Mr. Christie’s (1771). The title page reads that the book was written “by the author of the Remarks on the English Language”, which indicates that the Reflections must have been popular enough to serve as a recommendation for a new book.14 The book opens as follows:

This section, which follows upon a critical section on playacting and takes up some sixteen pages of the unnecessarily wordy and rather rambling (even by Baker’s own admission, 1770: xxvi) preface, is indeed one of the curious features in the book. Baker evidently decided it would be worth reprinting the observations in a separate publication a year later, announcing his plan to do so in the Reflections as well (1770:xxx). In the preface to the Reflections he also referred to an earlier book of his, “a Collection of Witticisms and Strokes of Humour”, published in 1766. Though writing that it was “what [he] then thought and still think[s] as diverting a Thing as ever appeared”, the book

So much for the trials of an aspiring author. Baker ends the preface by telling a few “witticisms” by way of advertising the book (“Some of the Copies are still remaining where these Remarks are sold. The Price is but a poor Shilling”, 1770:xliii).15 Baker’s Reflections even left its mark on several later grammarians. Vorlat (2001) discovered that “quite a few of his rules and examples were ... copied (directly or indirectly) by such grammarians as James Wood (1777), John Hornsey (1793), Alexander Bicknell (1796), John Knowles (1796) and William Angus (1800)”. The book had been reviewed at least twice in 1771, in the Monthly review and the Critical review (Percy 2008), and one of the reviews was by Dr John Hawkesworth (1715-1773),16 who had edited the official account of Captain James Cook’s voyages around the world (1773). Percy (1996) analysed the linguistic changes made by Hawkesworth to Captain Cook’s language, and the kind of changes he made to the text are very similar to those that filled Baker’s Reflections. It is therefore no surprise that Hawkesworth felt called upon to review the book when it came out.17 What little we have come to know about Baker on the basis of his publications and the contents of the preface to the Reflections suggests that he was a hack writer, who tried to find a market for books similar to his Reflections on the English Language, which contained remarks and observations about a variety of subjects - witticisms, usage problems, painting - which he thought might interest the general public and which might earn him some income as a result. It is significant, I think, that only the book on language proved successful, which seems due to the fact that it was published at the right moment in time, at a point in the history of the English standardisation process when there was (unbeknownst, it seems, to Baker) a demand for usage guides, particularly among the rising middle classes. And it is interesting that Baker’s book, as unusual and as impractical in its set up as it is, happened to be the first of its kind. 5. Lowth’s Short Introduction to English Grammar But Baker wasn’t quite unique in his approach or even, strictly speaking, the first to produce a guide to correct usage: a precursor may be found in Lowth, not in his grammar proper but in the footnotes to his section on syntax. These are very similar to what we find in Baker, as the following example illustrates:

One of the reasons for the enormous popularity of Lowth’s grammar was precisely these footnotes, as appears from the following letter, written almost immediately after the grammar was published. In this letter, the author clearly responded to the attitude to the question of linguistic correctness such as it transpired from the footnotes:

To modern readers, however, it is precisely these footnotes that gave the grammar such a bad press (Hussey 1995:154), as is evident from the negative perspective Lowth is generally placed in by writers such as Jean Aitchison in Language Change, Progress or Decay? (1981: 23-25, and later editions)or Bill Bryson in Mother Tongue (1990:132-133). Nowadays, Lowth is viewed, rather negatively, as an icon of prescriptivism (Tieken-Boon van Ostade forthc.), which is a far cry from the way his grammar was looked upon during the second half of the eighteenth century. The reason for this change in perception is in my view the following. Lowth’s grammar is a typical English grammar of the period: it deals with orthography, etymology, syntax and, instead of the usual section on prosody (Vorlat 2007:504), with punctuation. But the extensive notes on grammatical errors, primarily in the form of footnotes in the section on syntax, turn it into a normative grammar. In these notes Lowth illustrates rules and strictures in the text itself with examples taken from “the best authors” (1762:vii), thus illustrating grammatical errors committed by men like Swift, Lord Bolingbroke, Congreve, Hobbes and Prior - writers of stature who were all dead by this time (Percy 1997:134). His reason for doing so is to illustrate, as he wrote in his preface, that “every one who undertakes to inform or entertain the public [i.e. published authors], ... should be able to express himself with propriety and accuracy” (1762:ix). The notes, in other words, illustrate that this was far from the case with many authors of reputation, and that those with similar aspirations would do well to consult his grammar. Though not originally conceived of as such - the grammar had been written for his son Thomas Henry as an aid to prepare him for the study of Latin once he would be old enough to go to school - Lowth’s grammar came to have a normative function. It became so popular because a prescriptive approach to grammar, like that taken in the footnotes that dealt with usage problems, was what people looked for at this time of large-scale social and geographical mobility. But the grammar was also extremely popular among grammarians, and many of them copied its rules and strictures into their own grammars, making the rules more prescriptive as they did so. An example of this is the treatment of preposition stranding in the course of the eighteenth century analysed by Yañez-Bouza (2008). Lowth’s status as a prescriptivist is therefore largely the result of how others treated him and his grammar, not what he himself intended to be. Lowth was aware of the fact that his grammar was basically a practical grammar, that it dealt with language at the level of usage, not with grammar as an abstract system, for in his preface he wrote:

He thus clearly recognised the function of his own grammar, contrary to modern linguists, who blame him for being prescriptive rather than descriptive (see Pullum 1974 for a detailed analysis of this). In retrospect, demands are made by linguists today on grammars like the one by Lowth that are anachronistic, proceeding from the modern perspective of linguistics as a science, which did not apply in his day. Linguistics as a discipline did not exist in eighteenth-century England, and apart from the work of the speculative grammarians of the period, grammars were largely practical and normative in their outlook and approach to language. From the perspective of the standardisation process of the language as I have discussed it, Lowth’s grammar stands at the turning point of the change from the codification into the prescription stage, and this is most evident in its footnotes. The footnotes can be called an innovation in grammar writing, though Lowth may have picked up the idea of dealing with usage problems from the practice of exposing grammatical errors by writers in the Critical and the Monthly Reviews (cf. Percy 2008); doing so must have been a popular pastime among the readers of these periodicals, as is also clear from the letter quoted above: the author obviously enjoyed the game of “picking faults and finding Errors”. 6. Lowth, Baker and Fowler compared If Baker’s Reflections represent the birth of the usage guide, Lowth’s grammar, or its footnotes, can be called a usage guide in embryonic form. There are considerable similarities between the two works: to begin with, many strictures are the same, such as those against the mixed usage of you and thou, the use of fly for flee and lay for lie, whom for who and vice versa and so on. Neither author was afraid to attack mistakes in usage by what were considered to be the best writers, and both criticized Swift, a literary giant by reputation. But in the case of both, the authors attacked were no longer alive, which was probably an important safety precaution. In an age in which people with social ambitions had to depend on patronage - Lowth’s career is a good example of this (see Hepworth 1978:34) - one couldn’t be too careful. As with Baker, who made this explicit, Lowth’s usage was not based on his own linguistic preferences (contrary to Aitchison’s assumptions), as I found out when testing Lowth’s strictures against his own usage (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2006). Both men have a sense of humour when tackling their subject: I’ve provided several examples of this from Baker’s Reflections, but Lowth, too, when dealing with preposition stranding, wrote, tongue in cheek, that “This is an Idiom which our language is strongly inclined to” (1762:127-128). And both were so popular that they were copied by grammarians after them, though Lowth more so than Baker. There are similarities with Fowler, too, summarised in Table 1:

Table 1. Similarities between Lowth, Baker and Fowler. Fowler criticised authors of standing as well. In his section on preposition stranding, for instance, he mentions Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Dr. Johnson, the Bible, Burton, Pepys, Congreve, Swift, Defoe, Burke, Lamb, De Quincey, Landor, Hazlitt, Peacock, Mill, Kinglake, M. Arnold, Lovell, Thackeray and Kipling (Fowler 1926:459). (Of these, only Kipling was still alive in 1926.) Whether or not his norm of correctness had any relationship to his own usage I have not yet been able to ascertain. Similarly, to study his influence on other writers is something that still needs to be undertaken; I expect, however, that it must have been considerable. Fowler’s Modern English Usage was never published anonymously. The earlier Concise English Dictionary, however, had been published with only the Fowler brothers’ initials on the title page. Fowler’s decision to put his full name on the title page of Modern English Usage may have been inspired by similar motivations as Baker’s. In Lowth’s case, it was only towards the end of his life, when he noted in his Memoirs that his grammar had been printed in as many as 34,000 copies, which was considerably more than any of his other books, that he fully realised the popularity of the grammar (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2008a). Contrary to Baker and Fowler, Lowth did not use newspaper language as a source for his linguistic strictures, but he did, as I argued above, find inspiration for them in the periodicals of his day. Also contrary to Baker and Fowler, Lowth was not outside the mainstream of linguistics, such as it was in his time. As I will argue in the book on Lowth which will be published next year (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2010), there is much in his grammar which can be seen as a reaction against the authoritative Dictionary of the English Language (1755) by Dr Johnson. There is one further similarity between Lowth and Fowler which we do not find with Baker, at least, not to my knowledge, which is very likely due to the fact that he was less widely read than the other two. Neither Lowth nor Fowler are thought of very highly by linguists: in dealing with language at the level of usage rather than with linguistic structure, their work is not usually taken seriously.18 What is more, strictures are commonly attributed to Lowth and Fowler even when they had nothing to do with them. An example is the split infinitive, which only first arose as a linguistic criticism during the nineteenth century but which was attributed to Lowth on the website “Bishop Lowth was a fool” (Tieken-Boon van Ostade forthc.)19 and on another webpage on Lowth (Beal 2004:111-112). This similarly happens with Fowler. To commemorate his birthday, Denis Baron posted an entry on his blog Web of Language which stated that “Fowler’s that/which invention became a rule”. Richard Hershberger, one of the respondents to Baron’s entry, commented that

Like Lowth, Fowler has iconic status, and he is similarly credited with more in this respect than is actually due to him. 7. Conclusion Lowth, Baker and Fowler operated quite independently of each other. Baker never referred to Lowth, and as far as I can tell Fowler never referred to Lowth either20 or, indeed, to Baker. Interestingly, however, Burchfield in his edition of Modern English Usage does refer to Lowth, in connection with the use of only, and perhaps in other places, too. Though I have to investigate this in greater detail, I don’t on the whole think Burchfield’s edition is an improvement on Fowler’s original edition. One unfortunate change is the fact that he removed Fowler’s deliberate “flippancy”, which is, I think, one of the more attractive features in the original edition, as also one of the commentators in Dennis Baron’s blog notes. There is therefore no direct link between Lowth, Baker and Fowler, and yet they are all part of the same tradition, the tradition that gave rise to the English usage guide. So why are these three works, which were created quite independently of each other, so similar, both in the approach they took and in the items they deal with? I think the answer to this question is that they each in turn started to consider the same problem in the same way. The problem they were confronted with was that they perceived a need for guidance in linguistic matters among speakers and writers of English, which they saw exemplified by the poor usage, in grammar and in matters of idiom, even by authors of reputation, and as time went on in the language of newspaper in particular. It is this problem that they sought to address and that they approached in the same way. Their guides to correct usage served a purpose to those who felt the need to speak and write elegantly, typically the socially aspiring or linguistically sensitive middle classes. That the items they dealt with largely remained the same through time, even down to the most recent edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage of 1996, confirms the point of view presented in Milroy & Milroy (1985) that even though the language has been codified into grammars and dictionaries, it will never allow itself to be fixed. The prescription stage is an ongoing stage, and usage guides are its inevitable - and vastly interesting - product. References Aitchison, Jean. 1981. Language change: progress or decay? [repr. 1984; 2nd ed. 1991; 3rd. ed. 2001]. Bungay, Suffolk: Richard Clay (The Chaucer Press) Ltd. Alston, R.C. 1965. A bibliography of the English language from the invention of printing to the year 1800. Vol. 1. English grammars written in English. Leeds: E.J. Arnold and Son. Auer, Anita. 2008. “Eighteenth-century grammars and book catalogues”. In: Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), 2008:57-75. Ayres-Bennett, Wendy. 2002. “An evolving genre: seventeenth-century Remarques and Observations on the French language”. In: Rodney Sampson and Wendy Ayres-Bennett (eds.), Interpreting the history of French. A Festschrift for Peter Rickard on the occasion of his eightieth birthday. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi: 353-368. Baker, Robert. 1766. Witticisms and strokes of humour. London. Publisher? Baker, Robert. 1770. Reflections on the English language, In the Nature of Vaugelas’s Reflections on the French. London: J. Bell. Baker, Robert. 1771. Observations on the Pictures now in Exhibition at the Royal Academy, Spring Gardens and Mr. Christie’s. London: John Bell and G. Riley. Beal, Joan. 2003. “John Walker: prescriptivist or linguistic innovator?”. In Marina Dossena and Charles Jones (eds.), Insights into Late Modern English. Berlin: Peter Lang: 83–105. Beal, Joan C. 2004. English in modern times 1700–1945. London: Arnold. Bennett, Paul. 1996. Bennett’s wordfinder. A handy companion to the second edition of the world’s most famous book on modern English usage. Nerang, Queensland (Australia): Paul Bennett Publishing. Bryson, Bill. 1990. Mother tongue. The English language. London: Penguin. Burchfield, R.W. (rev.). 1996. Fowler’s Modern English usage [3rd edn; 1st edn 1929]. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chapman, Don. 2008. “The eighteenth-century grammarians as language experts”. In: Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), 2008:21-36. Crystal, David. 1995. The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language [repr. 1999], Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ECCO: Eighteenth Century Collections Online Thomson Gale. Fowler, H.W. 1926. A dictionary of modern English usage, Oxford: University Press. Haugen, Einar. 1966. “Dialect, language, nation”. American anthropologist 68:922-935. Repr. in J.B. Pride and Janet Holmes (eds.), Sociolinguistics. London: Penguin: 97-111. Hepworth, Brian. 1978. Robert Lowth. Boston: Twayne Publishers. Honey, John. 1997. Language is power. The story of Standard English and its enemies. London/Boston: Faber & Faber. Honey, John. 2000. “A response to Peter Trudgill’s review of Language is power”. Journal of sociolinguistics 4/2:316-319. Hussey, Stanley. 1995. The English language. Structure and development. London/New York: Longman. Jones, Charles. 2006. English pronunciation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, London: Palgrave Macmillan. Leonard, S.A. 1929. The doctrine of correctness in English usage 1700–1800. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin. Lowth, Robert. 1762. A short introduction to English grammar, London: A. Millar, and R. and J. Dodsley. McMorris, Jenny. 2001. The Warden of English. The Life of H.W. Fowler. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Michael, Ian. 1970. English grammatical categories and the tradition to 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Michael, Ian. 1991. “More than enough English grammars”. In: Gerhard Leitner (ed.), English traditional grammars, Amsterdam: Benjamins: 11-26. Michael, Ian. 1997. “The hyperactive production of English grammars in the nineteenth century: A speculative bibliography. Publishing history 41: 23–61. Milroy, James and Milroy, Lesley (1985), Authority in language: Investigating standard English, London: Routledge . Mossner, E.C. and I.S. Ross (eds.). 1987. The correspondence of Adam Smith. The Glasgow edition of the works and correspondence of Adam Smith. Vol. VI. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund. Nevalainen, Terttu and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. 2006. “Standardisation”. In: Richard Hogg and David Denison (eds), A history of the English language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 271-311. The Oxford dictionary of national biography online edition. The Oxford English dictionary online. Percy, Carol. 1996. “In the margins: Dr Hawkesworth’s editorial emendations to the language of Captain Cook’s Voyages”. English studies 77:549–578. Percy, Carol. 1997. “Paradigms lost: Bishop Lowth and the poetic dialect in his English Grammar”. Neophilologus, 81:129-144. Percy, Carol. 2008. “Mid-century grammars and their reception in the Monthly review and the Critical review”. In Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), 125–142. Pullum, G.K. 1974. “Lowth’s grammar: A re-evaluation”. Linguistics 137:63–78. Stammerjohann, Harro (gen.ed.). 1996. Lexicon grammaticorum. Who’s who in the history of world linguistics. Tübingen: Niemeyer. Sundby, Bertil, Anne K. Bjørge and Kari E. Haugland. 1991. A dictionary of English normative grammar 1700-1800. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. 2000. “Normative studies in England”. In: Sylvain Auroux, E.F.K. Koerner, Hans-Josef Niederehe and Kees Versteegh (eds.), History of the language sciences/Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaften/Histoire des sciences du langage, Volume 1. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter: 876–887. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. 2006. “Eighteenth-century prescriptivism and the norm of correctness”. In: Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los (eds.). The handbook of the history of English. Oxford: Blackwell: 539–557. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. 2008a. “The 1760s: grammars, grammarians and the booksellers”. In Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), 101–124. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. 2008b. “English grammars, grammarians and grammar-writing: an introduction”. In Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), 1–14. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid (forthc.). “Lowth as an icon of prescriptivism”. In: Raymond Hickey (ed.), Ideology and change in Late Modern English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid (in progress). The Bishop’s grammar. Robert Lowth and the rise of prescriptivism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid (ed.). 2008. Grammars, grammarians and grammar-writing in eighteenth-century England. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Truss, Lynne. 2003. Eats shoots and leaves. The zero tolerance approach to punctuation, London: Profile Books. Trudgill, Peter. 1997. Review of John Honey, Language is Power. Journal of sociolinguistics 2/3:457–461. Vorlat, Emma. 2001. “Lexical rules on Robert Baker’s ‘Reflections on the English language’”. Leuvense Vorlat, Emma. 2007. “On the history of English teaching grammars”. In Peter Schmitter (ed.), Sprachtheorien der Neuzeit III/2, Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag: 500–525. Yañez-Bouza, Nuria. 2008. “Preposition stranding in the eighteenth century: Something to talk about’, in Tieken-Boon van Ostade (ed.), 251-277.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||