Historical Sociolinguistics and Sociohistorical Linguistics

Up |

Tackling the Writer-Sender Problem: the newly developed Leiden Identification Procedure (LIP)* Judith Nobels and Marijke van der Wal (contact) (University of Leiden) Received October 2009, published October 2009

1. A treasure for historical linguists Examining the linguistic past from the perspective of the language history from below, historical linguists consider the language of proximity, found in egodocuments such as private letters and diaries, as an indispensable source for reliable data.1 Until recently, for the history of the Dutch language of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries linguists had to rely mainly on egodocuments written by men from the higher ranks in society. Egodocuments from women in general and from men and women of the lower and middle classes were available only in small numbers, scattered over various provincial, municipal and personal archives in The Netherlands.2 This situation changed considerably when historians rediscovered the Dutch documents in the High Court of Admiralty’s archives, kept in the National Archives (Kew, UK). Apart from a wide range of other material including treatises on seamanship, plantation accounts, textile samples, ships’ journals, poems and lists of slaves, this collection of so-called sailing letters comprises about 38,000 Dutch letters, both commercial and private, from the second half of the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries. These sailing letters were confiscated during the wars fought between The Netherlands and England. What makes this huge collection of letters so interesting for linguists are the 15,000 private letters, written by men, women and even children of all social ranks, including the lower and middle classes. The letters offer an unprecedented opportunity to gain access to the everyday and colloquial language of the past and will consequently enable linguists to get a view on the Dutch language history from below. At the University of Leiden, researchers of the large-scale programme Letters as loot. Towards a non-standard view on the history of Dutch explore this highly valuable source for the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries.3 In this paper we will focus on the challenges presented by the seventeenth-century material and discuss our fruitful collaboration with researchers from other disciplines. 2. Confiscated letters England and The Netherlands were rivals and enemies for centuries: as many as four Anglo-Dutch Wars were fought and in various other wars of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century England and the Netherlands stood at opposite sides. Warfare implied privateering (in Dutch kaapvaart): private ships (privateers) authorized by a country's government attacked and seized cargo from ships owned by the enemy. Privateering was a longstanding legitimate activity, practiced by all seafaring European countries and regulated by strict rules. The conquered ship and all its cargo, called a prize, were considered as loot for the privateer, if the rules had been followed by the book. In England it was the High Court of Admiralty (HCA) that had to establish whether the current procedures were properly followed. In order to be able to decide whether the ship was a lawful prize, all the papers on board, both commercial and private, were confiscated and claimed by the HCA. After the legal procedure, the confiscated letters stayed in the HCA's archives. That is how a huge number of Dutch letters from Dutch ships taken by privateers ended up stocked in hundreds of boxes in the British National Archives. To fully appreciate the enormous size of this collection it is important to note that in many cases the ships’ cargo contained a lot more mail than the crew’s own correspondence. Ships sailing to the Caribbean (West India) and to East India often took mailbags on board and thus functioned as mail carriers between The Netherlands and those remote regions, and vice versa (Van Vliet 2007: 47-55; Van Gelder 2006:10-15).

3. Daily practice: selecting letters and building an electronic corpus Before being able to analyze the linguistic data of the letters from a socio-historical perspective, we have had to address the complicated task of making a selection from the 15,000 private letters and to build an electronic corpus. We have chosen to make two cross-sections in the huge material, one for the seventeenth century (1664-1674) and the second one for the eighteenth century (1776-1784): these periods coincide with the second and third Anglo-Dutch Wars and with the fourth Anglo-Dutch War and the American War of Independence, respectively.5 From these two periods letters were selected and digital photos taken. These photos are being transcribed and with these transcriptions we are gradually building our electronic corpus.6 As a working tool a database, specially developed for our project, is available to store and retrieve all information on the letters. For linguistic searches we use the WordSmith tools, a concordance program developed by Mike Scott.7 A careful selection from the letters available for the two periods has to guarantee an appropriate representation of male and female writers, of different age groups and social classes. The regional origin of the writers will be taken into consideration too. The letters only provide us with the sender’s and addressee’s name and address, but more details can be found in marriage or baptism registers, kept in local archives. Those, however, are often incomplete - if they have been kept at all - and it is not surprising therefore that we often encounter difficulties in determining a sender’s age or social background.8 It is the huge number of letters that enables us to compile such representative corpora in spite of these frequent setbacks.9 In the selection process we take into account the contemporary circumstances of literacy and illiteracy. Although the rate of literacy in The Netherlands was high compared to that of other European countries at the time, part of the population could neither read nor write (Frijhoff & Spies 1999:237). Those who were able to read may not have had any writing skills, as reading and writing were taught in succession, not simultaneously (Blaak 2004: 13; Kuijpers 1997: 501; Van der Wal 2002: 9-13). Besides, those who learnt to write may have had little writing practice. So when Van Doorninck and Kuijpers (1993:14) calculate that in 1670 in Amsterdam 70% of the men and 44% of the women could write their own names, we must realize that some of these signers were probably not capable of producing anything more than just their signature (Frijhoff & Spies 1999:237). These full or semi-illiterates had to ask professional scribes (such as the ship’s writer or a public writer) or those in possession of writing skills (whom we will designate as social scribes) to write letters for them, if communication with loved ones was called for. To solve this major problem of distinguishing between self-writing senders and encoders we developed a procedure which combines script and content analysis. For part of the script analysis we benefited greatly from the expertise of artificial intelligence researchers, as will become clear below.

4. Tackling the writer-sender problem: various clues 4.1 Reference to the writing process In developing what we will hereby introduce as the "Leiden Identification Procedure" (LIP), we identified a number of form, content, and sender characteristics, clues that can reveal whether the letter is self-written (an autograph) or not. Explicit reference to the writing process is a first and an obvious content clue, but it does not occur very often. A convincing example is a letter written by a sailor to his father in which he explains his bad handwriting by referring to lying in his bunk due to illness:11 ende al ist wat qualick geschreven ick en kon dat nijet helpen want ick nogh ijn de koije lagh dat ick nogh niet eel ghenesen en was While this letter irrefutably shows that it is self-written, other letters prove the opposite. An example of such a letter is one written on behalf of Elisabeth Bernaers.12 It is written in the first person singular and signed with the name of Elisabeth Bernaers, but below this signature we find the line: ‘door mij gescreven maeij ken pieters ul dochter’ (written by me, Maaike Pieters, your daughter).

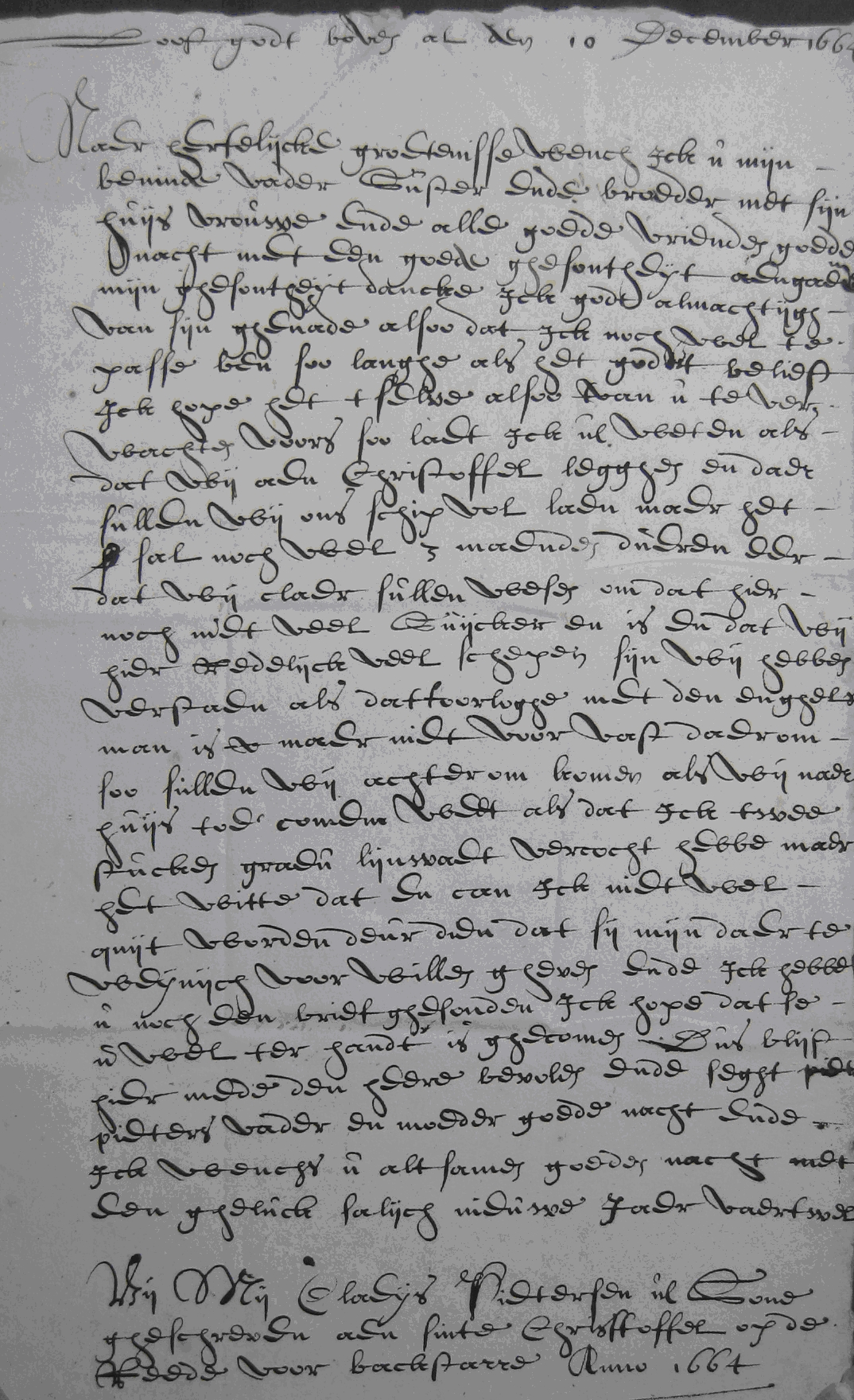

4.2 Identical handwriting and the GIWIS-programme A second clue is when we find two letters written in the same hand, but sent by different people, in which case at least one of the letters is non-autographical. Illustrative examples are two letters written on 10 December 1664 in Saint-Kitts, in the roadstead of Basseterre.13 Although the first letter in figure 2 is signed with the name of Claeijs Pietersen and the second is supposedly signed by Jan Lievensens, the handwriting and lay-out of the letters are so similar that both of them must have been written by one and the same person. The similarity is particularly striking in the header and in the closing formula of the letters.

Since the content of the letters does not indicate that one of the senders is better educated or of a higher rank than the other, and since the letters have been written aboard a ship, in very neat and professional handwriting, we are tempted to assume that a third person (maybe the ship’s writer, the clergyman or one of the petty officers) wrote the letters for both Claeijs and Jan. Although in this case we cannot know for certain who the writer was, it is clear enough that we should not mark these letters as autographs. We have to bear in mind that this ‘same hand clue’ can only be applied if enough letters are available to compare the handwritings of letters written around the same time in the same area. Of course, this clue cannot give a decisive answer about the status of letters that cannot be linked to other epistles in this way. We have to allow for the possibility that letters from different senders and written by the same scribe have not survived or have not been discovered yet. Since comparing the handwriting of different letters takes up a considerable amount of time, we are fortunate to benefit from the expertise of a team of artificial intelligence specialists at the University of Groningen. This team, under the direction of Prof. L. Schomaker, has developed a computer program that is able to compare a sample of handwriting to a large set of handwritings and identify similar samples. This Groningen Automatic Writer Identification System (GRAWIS) was originally meant for forensic purposes, but with a few modifications it can also be applied to historical texts (Bulacu 2007, Bulacu & Schomaker 2007a, Bulacu & Schomaker 2007b). A modified version of this programme, called GIWIS (Groningen Intelligent Writer Identification System), was developed for us by Axel Brink. GIWIS allows us to compare the handwriting of one specific letter to an entire set of letters. After the necessary preparatory work (which involves uploading pictures into the programme and selecting sections of the pictures that are suitable for processing), GIWIS selects ten samples that resemble the handwriting under investigation with just one click of the mouse. The program can compare handwriting using different features, such as the slant of the script and the thickness of the quill strokes. At this stage, the powers of perception of the researcher come in, for the program always lists samples that are supposed to show similar handwriting, even if there is barely any overlap between samples. It is therefore the researchers’ responsibility to check whether one of the listed ‘matches’ is a real match. Although human beings are still undoubtedly better at recognizing matching handwritings, computers are quicker at scanning large sets of examples. Using the GIWIS program wisely might save us a lot of time without necessarily affecting our conclusions for the worse. Not only the handwriting between letters can be compared, but also the handwriting within one and the same letter can be scrutinized in order to establish whether the letter is an autograph or not. If the sender’s name or signature at the bottom of the letter differs remarkably from the body of the letter, the sender may not have written the letter him/herself. This is certainly the case if the handwriting in the letter itself is rather neat and steady while the signature shows an inexperienced hand. It is very likely – because of the education circumstances sketched above – that there were people whose writing experience was only barely sufficient to sign their name, but who were not able to produce an entire letter (Frijhoff & Spies 1999:237). Apparently, some senders wanted to sign the letters that had been written for them, maybe from a point of honour, as a proof of authenticity, or as a more personal sign of life. Although this third clue can sometimes offer convincing proof of the non-autographical nature of a letter, it is to be handled with caution, for it seems to be the case that experienced writers sometimes used a larger handwriting for their name or signature as part of their stylistic habit (e.g. Figure 4).14 A seemingly different handwriting in the sender’s signature therefore does not always point to a different identity for sender and writer. The letter might have been written by an experienced writer who wanted to emphasize his/her signature by using a larger or somewhat different hand. Only if the signature seems to have been written by a less experienced writer than the person who wrote the body of the letter can we be certain that we are dealing with a non-autograph (see for instance Figure 5 as an example of this).

4.3 Occupation and Social Rank The fourth clue is related to the occupation and social status of the writer. If the letter’s contents reveal enough about the life of the sender for us to determine his/her occupation, we can estimate how likely it is that the sender of the letter was an experienced writer. Captains, helmsmen, salesmen, doctors, lawyers, book keepers, clergymen, ship’s writers, and similar people had to possess writing skills in order to study or carry out their profession (Van Doorninck & Kuijpers 1993: 46-50; 58-61). These occupations are typical of men. For women it is more difficult to determine whether they needed to be able to write. They rarely mention anything in the letters about the jobs they might have had in order to secure an additional income, but we may assume that a lot of these jobs involved some kind of domestic work or retail trade, which did not require writing skills (De Wit 2008: 148-149). Wives of captains and skippers may be an exception: when their husbands were at sea, a lot of them were responsible for these seamen’s businesses and part of their administration, and it would probably have been more difficult for these women to handle all the paper work if they themselves could not write (De Wit 2008: 161-162, Bruijn 1998: 67).15 People of a higher social rank are also very likely to be experienced writers, because it is plausible that their parents were wealthy enough to offer them an education that included the costly writing instruction (Frijhoff & Spies 1999: 238). A man’s social rank can thus be determined through his occupation or his title; for a woman’s social rank, we rely on the social rank of her husband or family.16 Although the fact that these people could write does not necessarily mean that they actually wrote their private letters themselves, we nevertheless assume that they did if there is no proof otherwise. Just like all the other clues, this fourth clue has to be used carefully too. The fifth clue is very closely connected to the previous one; it is in fact an elaboration upon the fourth one. If we can find out a sender’s social status, we can compare the level of experience of the handwriting and the number and nature of corrections in the letter to the expected level of education.17 Neatly written letters of low ranking senders are of particular interest: they may well be non-autographical. Clearly, however, this clue is problematical in two ways. Is it always possible to tell the difference between an experienced, but sloppy hand and an inexperienced one? Secondly, we might be at risk of falling into the trap of circularity. It is of vital importance to avoid creating our corpus based on expectations about the language use of people of a certain rank, because that is exactly what we want to research. This clue needs to be restricted to our expectations about the handwriting, i.e. about the way in which people wrote, not about what they wrote (the language use). The last and most objective way to determine whether a letter’s writer and sender are the same person is to compare the handwriting and/or signature used in the letter with other samples of the sender’s handwriting that are known to be authentic. It is not always easy to find these samples, but it is possible. For certain cities which kept their archives well, we can retrieve a surprising number of signatures with the help and advice of archivists. 5. Searching the archives for authentic signatures The seventeenth-century sources that can offer authentic signatures or handwriting samples differ in various regions. In Amsterdam, for instance, newly weds were requested to sign the marriage register; in Rotterdam, the names of the newly weds were recorded by the clergyman in charge of the ceremony. The latter practice makes the Rotterdam marriage registers unsuitable for our search for authentic signatures. Luckily, the Rotterdam municipal archives keep about half a million notarial acts dating from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries which offer us a good chance of retrieving authentic signatures.18 In the cities of Middelburg and Vlissingen in the province of Zealand the situation is more complicated. Many of the seventeenth-century Zealand archives have been lost, among which the registers of the city of Middelburg. In Vlissingen, the few remaining marriage registers do not contain any signatures, but the information in the archive of the Audit Office of Zealand is more promising.19 The Audit Office of Zealand kept a detailed track of the expenses of the admiralty of Zealand. Salesmen who had delivered goods or people who had worked for the Zealand admiralty, had to send a request to the Audit Office in which they described what they had done and how much they expected to be paid. If the request was approved by the Audit Office, the creditor could collect his money and had to sign for receipt on the same document that had originally been sent in as request. All these documents have been kept in the enormous archive of the Audit Office of Zealand. It contains a wealth of signatures and samples of handwriting not only of sailors, soldiers, merchants and labourers, but also of their relatives who collected their wages. Sadly enough, a detailed inventory of the Audit Office’s archive is not available.20 Although this makes a targeted search almost impossible, we succeeded in retrieving a couple of authentic signatures from senders of our letters. One of them is Jacob van de Velde, who sent a letter to his wife and added a signature with distinctive flourishes (see Figure 6 below21). In the Audit Office’s archive we found his request for a delivery of wine and other goods, written in a similar handwriting and signed with the unmistakably identical signature (see Figure 7 below). In this case we can convincingly identify Van de Velde’s letter as autographical.

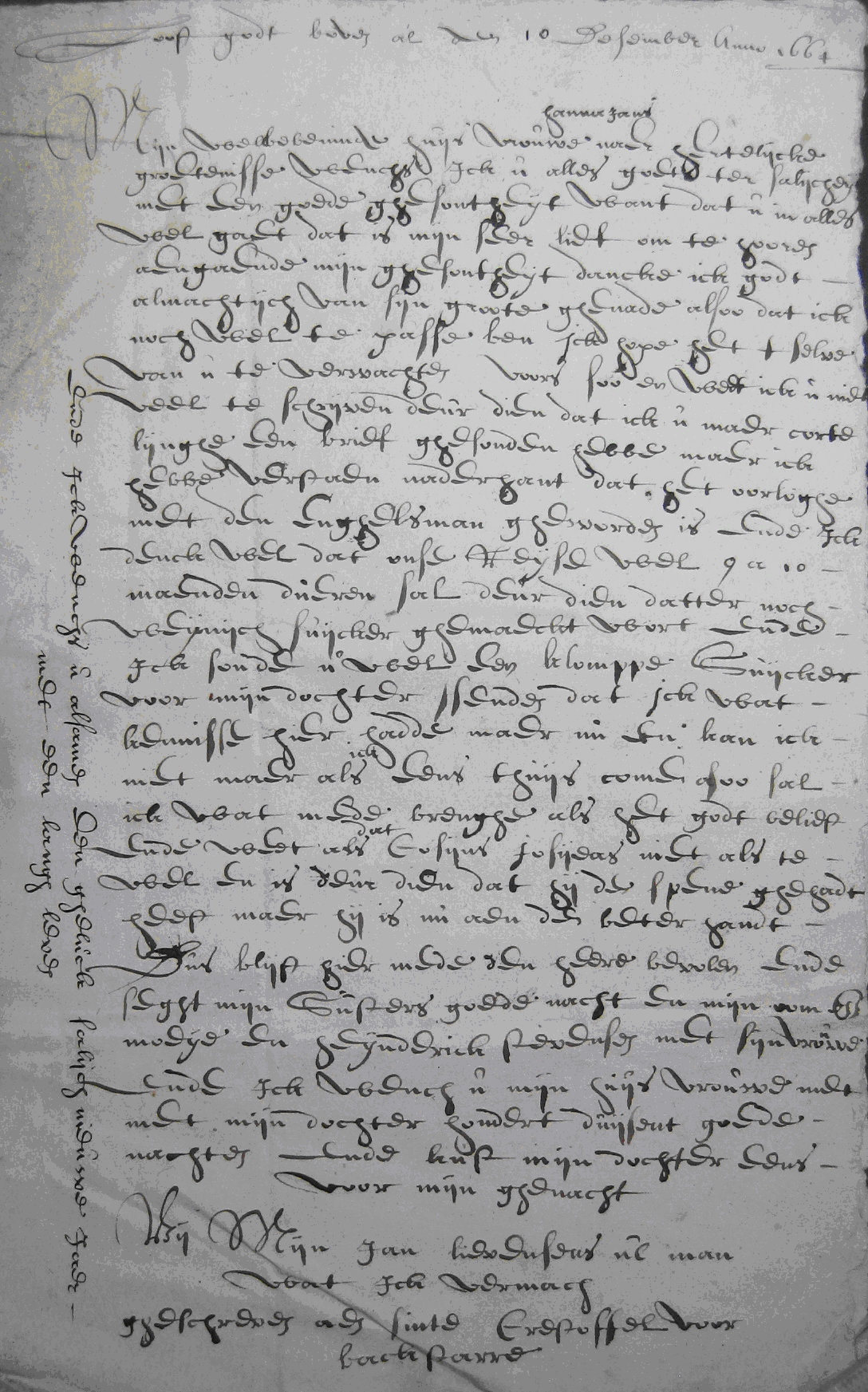

6. Combining the Clues Some of the above-mentioned clues are very telling, while other clues only become important if a number of other indications cannot provide conclusive results. To visualize this we transformed the list of clues into a flow chart (Figure 8) that takes different priorities into consideration and that allows us to examine every letter thoroughly, as well as efficiently in the approach. The flow chart starts with the content of the letter. If it mentions explicitly that the letter is not self-written or self-written (Boxes 1 and 2), we need not look for further evidence and can go straight to the relevant conclusion (A or B). If the content does not offer any information about the writing of the letter, we should check our corpus for letters in the same handwriting, but sent by someone else (Box 3). If we find such letters, we can check whether they were all sent by people of low status, but written in an experienced hand (Box 4). If this is the case, chances are high that we are dealing with letters written by a professional writer (C). If they are not all neatly written letters sent by people of low status, we can only learn more about the potential writer if we look for signatures or handwriting samples of the senders concerned (conclusion D).

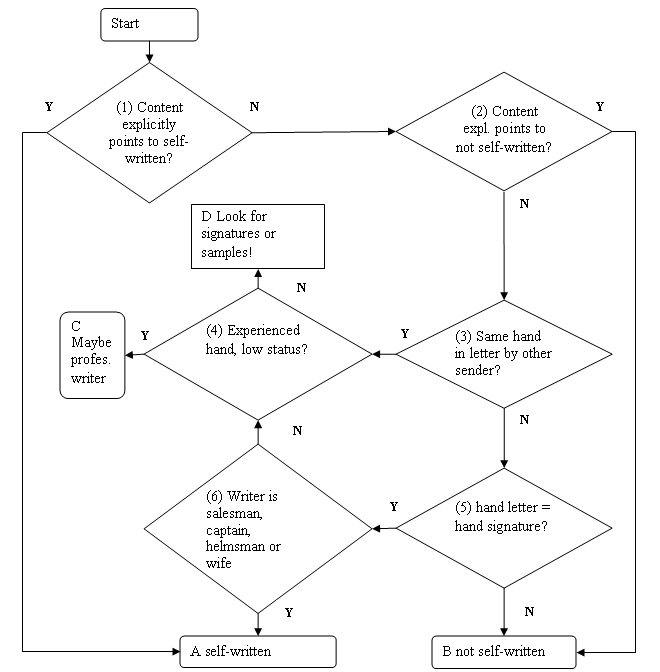

If the letter is the only letter in our corpus which shows a certain hand, we can scrutinize the signature (Box 5). If it is not written in the same hand as the body of the letter and if it seems to be written in a less experienced hand, we are probably dealing with a non-autographical letter (B). If the hand in the signature does not seem to be different from that in the rest of the letter, it is time to take into account the occupation and social status of the sender (Box 6). As we have seen before, if the writer is a salesman, a captain, a helmsman, a lawyer, a doctor, a clergyman, a ship’s writer, someone of high social status, or his wife or child, it is quite probable that the letter is autographical (A). If the sender of the letter falls into neither category, the only option left is to compare the sender’s handwriting with what we would expect of someone with his/her status (box 4). If the handwriting is very neat, while the sender is of low status, it might be possible that a professional writer or a friend who was an experienced writer interfered (C). If the handwriting does not seem to be very deviant from what we would expect, the letter might be self-written. But because the writer could have been a non-professional writer as well, the only way to find out for certain is to look at authentic samples of handwriting or signatures, (D). The letters that fall into category A are identified as autographical, those of categories B and C as non-autographical. The letters in category D might prove to be either autographical or non-autographical or letters with an uncertain status, depending on the authentic handwriting samples or signatures that can be traced. We tested this working method on thirty letters that were written in 1664 on the island of Saint-Kitts (see Figure 9), which was then known as Sint-Christoffel to the Dutch. Twenty of the letters were positively identified as autographical (among which the letter written by Jacob van de Velde), two letters were identified as non-autographical (the letters written by Claeijs Pietersen and Jan Lievensens), and we were left with eight letters that have an uncertain status because we could not find any authentic signatures or samples to back up our assumptions.

Two more remarks about our procedure have to be made. Firstly, if particular striking clues occur in a letter at first sight, there is no harm in skipping steps in the flowchart. The chart's chief purpose is to help us analyze letters that do not immediately signal whether they are autographical or not. Secondly, it needs to be remembered it is not always possible to be one hundred percent certain about the status of a letter without the evidence of authentic handwriting or signature samples. 7. Concluding comments and research perspectives The Leiden Identification Procedure presented here enables us to distinguish three categories of letters in our corpus: autographical, non-autographical and letters of uncertain status. This achievement has major consequences for our research. It enables us to build a reliable corpus of autographical letters that is fit for our historical sociolinguistic research, a corpus that will allow us to relate linguistic characteristics to social variables such as age, gender and social status. The non-autographical and uncertain letters should be kept well apart from the autographical letters to avoid working with linguistic material that is unsuitable for our research aims. Evidently, if some senders did not write their letter themselves, their social characteristics cannot be related to the language use in the letter. Moreover, since it is impossible to distinguish between the input of the sender and that of the encoder, it is dangerous to link the professional or social scribe’s social variables (if known at all) to the language use of the letter. The non-autographical letters unsuitable for our analysis can nevertheless serve a different purpose: they allow us to examine encoding by Dutch professional and social scribes, a widespread practice which until now has never been examined systematically. Keeping professional scribes apart from social scribes (friends or family of the sender who were not professional writers), we may discover whether these groups use different encoding strategies. Again it is not an easy task to distinguish professional from social writers, but the level of experience of the handwriting and the number of letters written by the same scribe might be good indicators. If in the end this line of research delivers clear-cut differences between non-autographical and autographical letters, these results could be useful to reduce the category of uncertain letters. The letters with an uncertain status should be kept apart from the autographical and the non-autographical subcorpora, as they can be used neither for sociolinguistic research nor for research into encoding practices. There is no urgent reason why we should try to include these letters into our research project. Even after discarding the uncertain letters, we will still have ample letters at our disposal to conduct reliable sociolinguistic research and research into encoding practices. The possibility that a considerable number of seventeenth-century private letters in our corpus could be non-autographical need not be an impediment for our socio-historical research. In this paper we have shown that it is feasible to distinguish autographical letters from non-autographical letters in many cases. Determining whether letters are self-written or not is obviously of vital importance to an analysis of their language. It needs to take place before the actual linguistic research can start, because without the knowledge of the autographical status of the letters we could easily draw false conclusions about the historical sociolinguistic situation. It is important to note that in applying the procedure outlined here we benefited greatly from interdisciplinary research and extensive collaboration with archivists, historians and artificial intelligence specialists. In this case crossing the boundaries of our linguistic discipline has proven to be essential to lay a solid base for a reliable historical letter corpus that will give us access to the everyday and colloquial language of the past and broaden our view on the language history from below. References Blaak, Jeroen. 2004. Geletterde levens. Dagelijks lezen en schrijven in de vroegmoderne tijd in Nederland 1642-1770. Hilversum: Verloren. Bruijn, Jaap. 1998. Varend verleden. De Nederlandse oorlogsvloot in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw. Amsterdam: Balans. Bulacu, Marius. 2007. Statistical pattern recognition for automatic writer identification and verification. PhD thesis. Groningen: Artificial Intelligence Institute, Universiteit Groningen. Bulacu, Marius & Lambert Schomaker. 2007a. ‘Text-independent writer identification and verification using textural and allographic features’. In: IEEE Trans on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (PAMI), Special Issue – Biometrics: Progress and Directions 29/7. 701-717. Bulacu, Marius & Lambert Schomaker. 2007b. ‘Automatic handwriting identification on medieval documents’. In: Proceedings Of the 14th International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing (ICIAP 2007). 279-284. Croiset van Uchelen, Ton. 2005. Vive la Plume. Schrijfmeesters en Pennekunst in de Republiek. Amsterdam: De Buitenkant/ Universiteitsbibliotheek. Deursen, Arie van. 2006. Een dorp in de polder. Graft in de zeventiende eeuw. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker. Doorninck, Marieke van & Erika Kuijpers. 1993. De geschoolde stad. Onderwijs in Amsterdam in de Gouden Eeuw. Amsterdam: Historisch Seminarium van de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Dossena, Marina. 2008. ‘Imitatio literae. Scottish emigrants’ letters and long-distance interaction in partly-schooled writing of the 19th century’. In: Socially-conditioned Language Change: Diachronic and Synchronic Insights. 79-96. Dossena, Marina & Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. 2008. ‘Introduction’. In: Studies in Late Modern English Correspondence: Methodology and Data. Bern: Peter Lang. 7-16. Elspass, Stephan. 2007a. ‘A twofold view ‘from below’: New perspectives on language histories -and language historiographies’. In: Stephan Elspass e.a. (eds.). Germanic Language Histories ‘from Below’ (1700-2000). 3-9. Elspass, Stephan. 2007b. ‘‘Everyday language’ in emigrant letters and its implications for German historiography – the German case’. In: Multilingua 26. 151-165. Elspass, Stephan, Nils Langer, Joachim Scharloth & Wim Vandenbussche (red). 2007. Germanic Language Histories from Below (1700–2000). Berlin/ New York: De Gruyter. Frijhoff, Willem & Marijke Spies. 1999. 1650. Bevochten eendracht. Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers. Gelder, Roelof van. 2006. Sailing Letters. Verslag van een inventariserend onderzoek naar Nederlandse brieven in het archief van het High Court of Admiralty in The National Archives in Kew, Groot-Brittannië. Den Haag: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Kuijpers, Erika. 1997. ‘Lezen en schrijven. Onderzoek naar het alfabetiseringsniveau in zeventiende-eeuws Amsterdam’. In: Tijdschrift voor Sociale Geschiedenis 23/4. 490-522. Métayer, Christine. 2000. Au tombeau des secrets. Les écrivains publics du Paris populaire, Cimetière des Saints-Innocents, XVIe-XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Albin Michel. Scott, M. 2008. WordSmith Tools version 5. Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software. Vliet, Adri van. 2007. ‘Een vriendelijcke groetenisse.’ Brieven van het thuisfront aan de vloot van De Ruyter (1664-1665). Franeker: Van Wijnen Wal, Marijke van der. 2002. ‘De mens als talig wezen: taal, taalnormering en taalonderwijs in de vroegmoderne tijd’. In: De zeventiende eeuw 18. 3-16. Wal, Marijke van der. 2006. Onvoltooid verleden tijd. Witte vlekken in de taalgeschiedenis. Amsterdam: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen. Wit, Annette de. 2008. Leven, werken en geloven in zeevarende gemeenschappen. Schiedam, Maassluis en Ter Heijde in de zeventiende eeuw. Amsterdam: Aksant. Websites: Brieven als Buit / Letters as Loot: www.brievenalsbuit.nl Koninklijke Bibliotheek / The Royal Library, Sailing Letters : www.kb.nl/sl/index.html Metamorfoze: www.metamorfoze.nl/ WordSmith Downloads: www.lexically.net/downloads/version5/HTML/index.html WordSmith General Information: www.lexically.net/wordsmith/index.html. Zeeuws Archief / The Archive of Zealand: www.zeeuwsarchief.nl. * This article is a concise version of the more elaborate ‘Linking Words to Writers: Building a Reliable Corpus for Historical Sociolinguistic Research’ which will be published in the proceedings of the HiSoN-conference Language and History, Linguistics and Historiography (Bristol 2 to 4 April 2009). These proceedings are expected to be published by De Gruyter in 2011. 2. In this article we use the term social class as a synonym of social rank and not in its nineteenth-century meaning. 3. The research programme Letters as loot. Towards a non-standard view on the history of Dutch was initiated by the programme leader Marijke van der Wal (chair History of Dutch, Leiden University). It started on 1 September 2008, funded by NWO (The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research). Up-to-date information on the research project can be found on the website http://www.brievenalsbuit.nl (Dutch and English versions). 4. Cf. van Gelder’s report (Van Gelder 2006). The inventory is available now at the website of the Royal Library in The Hague (http://www.kb.nl/sl/index.html). 5. The cross-sections correspond with two subprojects of our programme: Everyday Dutch of the lower and middle classes. Private letters in times of war (1665-1674), a PhD-project carried out by Judith Nobels, and A perspective from below. Private letters versus printed uniformity (1776-1784), Tanja Simons's PhD-project. In the third subproject Rewriting the language history of Dutch, the post-doc Gijsbert Rutten and the project leader Marijke van der Wal intend to compare the two periods and to evaluate the ultimate results of examining the sailing letters. 6. Anticipating that transcribing hundreds of letters from scratch would be too time-consuming, Marijke van der Wal started the Wikiscripta Neerlandica project in 2007. Participants in this volunteer project provide first transcriptions, which are checked three times by different members of the Letters as Loot team before they are accepted as final transcriptions for the electronic corpus. 7. WordSmith Tools is an integrated suite of programs. The WordList tool produces a list of all the words or word-clusters in a text, set out in alphabetical or frequency order. The concordancer, Concord, is able to produce the context of a word or phrase in a text. The KeyWords tool lists the key words in a text. (http://www.lexically.net/downloads/version5/HTML/index.html. We use WordSmith version 5.0. (Scott, M., 2008, WordSmith Tools version 5, Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software) All information and downloads can be found on http://www.lexically.net/wordsmith/index.html. 8. Sometimes the letter itself does not even provide us with the sender’s and addressee’s full name and address. And to make matters even more complicated, seventeenth-century surnames were more often than not patronymic while some first names - like Jan, Cornelis, Claes, Pieter and Jacob for men, and Trijn, Mary, Neel, Guurt, Griet and Anna for women - were very frequent (Van Deursen 2006: 31-33). 9. Important criteria for sociolinguistic research will be amply met with at least a hundred (probably more) carefully selected letter writers in each corpus. 10. Note our use of the terms sender, writer, scribe, and encoder. The sender of the letter is the person in whose name the letter is written, the person whose thoughts are conveyed in the letter. The scribe or writer of the letter is the person who performed the mechanical act of writing the letter. Sometimes the scribe of a letter is not its sender, for instance when the sender of the letter is illiterate and has paid a professional writer to produce the letter. In these cases, we call the writer of the letter an encoder. An encoder is a person who has written a letter for someone else. It is important to note that our use of the term encoder differs from the use in Dossena (2008) and Dossena and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2008). 15. Evidence for this is also to be found in some sailing letters. Cf. the letters of Katelynen Haexwant to her husband Leendert Ariensen Haexwant, rear admiral, in which she informs him about financial matters (Van Vliet 2007: 314-333). 17. ‘The level of experience’ of a handwriting is a subjective criterion to some extent, but we believe that it is possible to distinguish different levels of experience based on various features such as whether the letters have been drawn graph by graph or not, the regularity of the handwriting in form and size, and whether the lines slope or not. 19. We are indebted to Albert Meijer of the Zealand Archive (het Zeeuws Archief) for the information he provided about the Audit Office of Zealand and his kindness and perseverance in helping us in our search for signatures and handwriting samples. More information about the archive of the audit office (Rekenkamer van Zeeland) is to be found on the website of the Zealand Archive. 20. Currently, within the Metamorfoze-project, an inventory is being made for a small part of the archive, linked to business in Suriname, but at present, July 2009, it is not clear whether a further inventory will follow. For the Metamorfoze-project cf. http://www.metamorfoze.nl |

||||||||||||||||||

|